diff options

Diffstat (limited to '_posts')

| -rw-r--r-- | _posts/2024-03-20-rf-primer.md | 752 |

1 files changed, 0 insertions, 752 deletions

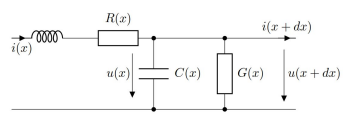

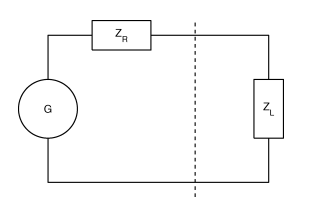

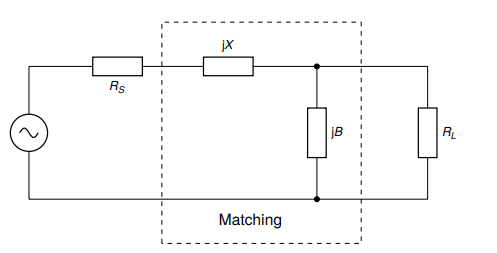

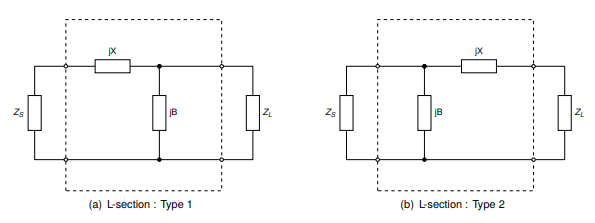

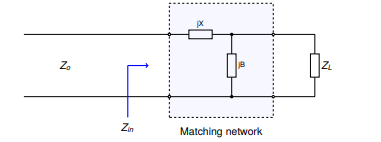

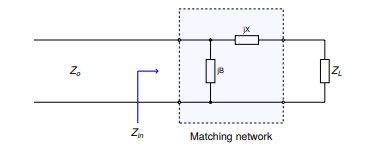

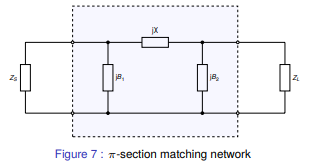

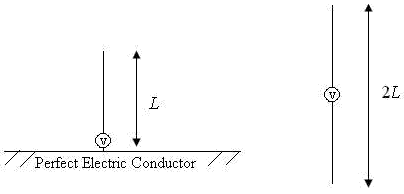

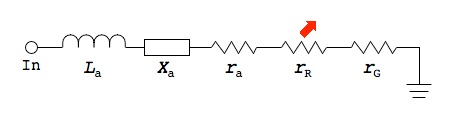

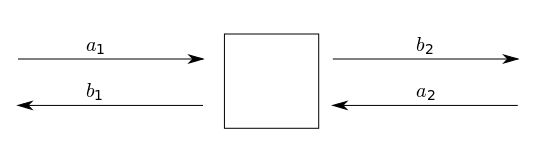

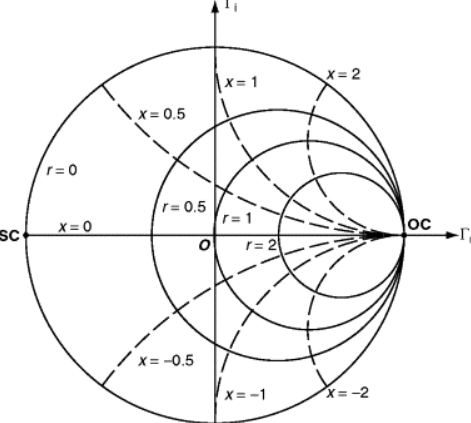

diff --git a/_posts/2024-03-20-rf-primer.md b/_posts/2024-03-20-rf-primer.md deleted file mode 100644 index cda19cc..0000000 --- a/_posts/2024-03-20-rf-primer.md +++ /dev/null @@ -1,752 +0,0 @@ ---- -layout: post -title: RF Circuit and Power Amplifier Design Basics -author: Dylan Müller ---- - -> A short primer on some of the basic concepts related to `RF` circuit -> and `RF` power amplifier design. - -1. [Average Power](#average-power) -2. [Transmission Lines](#transmission-lines) -3. [Impedance Matching](#impedance-matching) -4. [Electromagnetic Transducers](#electromagnetic-transducers) -5. [S-Parameters](#s-parameters) -6. [Harmonic Balance](#harmonic-balance) -7. [Lumped and Distributed Element Networks](#lumped-and-distributed-element-networks) -8. [Classes Of Operation](#classes-of-operation) -9. [Stability Analysis](#stability-analysis) -10. [Efficiency](#efficiency) -11. [P1dB Compression Point](#p1db-compression-point) -12. [Load Pull](#load-pull) -13. [LC Filtering](#lc-filtering) - -# Foreword - -The aim of this journal entry is to review some basic technical concepts -pertaining to general `RF` circuit design and modelling as well as `RF` power -amplifier design. - -`RF` circuit design is typically not covered in detail at an undergraduate level -and the author hopes that this journal entry will provide some useful -information to readers not familiar with the subject. - -# Average Power - -In order to be successful in `RF` power amplifier design, it is necessary to -understand `AC` power from both a frequency and time domain perspective. - -In the frequency-domain, complex `AC` power ($$S$$) is given by: - -$$ S = \overline{V}.\overline{I}^* $$ - -Where $$\overline{V}$$ and $$\overline{I}$$ are the voltage and current phasors. In -`RF` power amplifier design we are typically concerned with maximizing the real -component of complex power $$\Re(S)$$ which represents power dissipated in a load -such as an antenna (modelled by it's radiation resistance). The imaginary part -of $$S$$ represents reactive power which does not perform any useful work. - -Average real power ($$P_{avg}$$) is the industry standard measure of power for `RF` -and `microwave` systems and is measured in the `SI` units of `watts (W)`. Average -power over total time ($$T$$) for a continuous-wave (`CW`) signal is defined by the -following time-domain integral: - -$$ P_{avg} = \frac{1}{T} \int\limits_0^T v(t).i(t) dt $$ - -The terms $$v(t)$$ and $$i(t)$$ can then be expanded: - -$$ v(t) = v_{p}sin(2\pi ft), i(t) = i_{p}sin(2\pi ft + \theta) $$ - -Here $$\theta$$ represents the phase angle between $$i(t)$$ and $$v(t)$$ and ($$v_{p}$$) -and ($$i_{p}$$) represent the peak values of the voltage and current waveforms. - -It can be shown that for purely sinusoidal voltage and current waveforms: - -$$ P_{avg} = \frac{1}{2}v_{p}i_{p}cos(\theta) $$ - -Hence maximum real power is obtained when the current and voltage waveforms are -in phase. $$cos (\theta)$$ is commonly referred to as the power factor and this -constant relates real power to apparent power $$\|S\|$$. Apparent power is the -total complex power available to a particular load. - -In practice average real power is specified in terms of decibels referenced to `1` -`milliwatt (mW)` ($$dBm$$): - -$$ dBm(P) = 10\log_{10}(\frac{P}{1mW}) $$ - -While relative power is measured in decibels ($$dB$$): - -$$ dB(P) = 10\log_{10}(\frac{P}{P_{ref}}) $$ - -## Transmission Lines - -Traditional lumped circuit theory is only applicable to low frequency circuits -as it assumes that wires are lossless with negligible electrical length. -Electrical length is usually measured in terms of multiples of the wavelength -($$\lambda$$) of the highest frequency signal that is conducted over the line. - -As a rule of thumb, when the length of a wire is greater or equal to -$$\lambda/10$$, the voltage and current in the wire as a function of position -along the wire will no longer be constant with time and wave-like behaviour such -as reflection and standing waves start becoming important. In these cases -utilizing a distributed model, such as the transmission line, often becomes -necessary. - -Let $${u}$$ and $${i}$$ represent the voltage and current along the transmission line as -a function of position and time: - -$$ u = u(x,t), i = i(x,t) $$ - -Then at distance $${x+dx}$$ voltage and current can be expressed with a taylor -series expansion: - -$$ u(x + dx) = u(x,t) + \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} dx $$ - -$$ i(x + dx) = i(x,t) + \frac{\partial i}{\partial x} dx $$ - -A segment of a traditional transmission line is shown in the figure below. It -consists of a series distributed resistance $$R(x)$$, inductance $$L(x)$$ as well as -segment capacitance $$C(x)$$ and conductance $$G(x)$$. A transmission line is -thought of as a continuous series of these segments. - - - -It can be shown that the equations that describe changes in the voltage and -current on the line is given by: - -$$ \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} dx = -Ri - L \frac{\partial i}{\partial t} $$ - -$$ \frac{\partial i}{\partial x} dx = -Gu - C \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} $$ - -The equations above are known as the telegrapher's equations. These two -equations can be combined to produce two partial differential equations with one -isolated variable each ($${u}$$ or $${i}$$). - -$$u$$ and $$i$$ are related by the characteristic impedance ($$Z_{0}$$) of the -transmission line which can be derived from the telegraphers equations: - -$$ Z_{0} = \frac{V^+(x)}{I^+(x)} = \sqrt{\frac{R(x)+j\omega L(x)}{G(x)+j\omega -C(x)}} $$ - -For most transmission lines dielectric and conductor losses are low, so we -assume: - -$$ R(x) \ll j\omega L(x), G(x) \ll j\omega C(x) $$ - -As a result the equation above simplifies to: - -$$ Z_{0} = \sqrt{\frac{L(x)}{C(x)}} $$ - -It is worth noting that characteristic impedance $$Z_{0}$$ of a transmission line -only has an effect at `RF` frequencies. It is not possible to measure the -characteristic impedance of a transmission line directly with a multimeter -because resistance (ohms law) and characteristic impedance (electromagnetic -property) are not the same concept. - -Examples of transmission lines include coaxial cable and microstrip line. -Transmission lines typically have a characteristic impedance of `50` $$\Omega$$ in -`RF` systems and are used to carry `RF` signals from one point in a circuit to -another with minimal losses. - -# Impedance Matching - -It is often said that impedance matching is what truly differentiates `RF` circuit -design from low frequency circuit design. Indeed, it is one of the most common -tasks for an `RF` designer. - -`RF` signals travelling along a transmission line can be thought of as -electromagnetic power waves. Power waves are a hypothetical construct, one of -the many possible linear transformations of voltage and current. - -The figure below shows a typical `RF circuit` consisting of a `RF` power source -($$G$$) with an impedance of ($$Z_{R}$$) and a load with an impedance of $$Z_{L}$$. -The interface of the generator and load impedance is indicated by the dotted -line. - - - -It is at this interface that we experience reflection of the power wave (back to -the generator) when $$Z_{R} \neq Z_{L}$$. If the impedance of the generator and -load were equal then no reflection occurs. - -In general, the goal of an `RF` system is to transfer `RF` power as efficiently from -one point to another with minimal reflections. The degree of an electromagnetic -power wave reflected (at the boundary) is determined by the reflection -coefficient ($$\Gamma$$): - -$$ \Gamma_{L} = \frac{Z_{L} - Z_{0}}{Z_{L}+Z_{0}} $$ - -A $$\Gamma$$ of $$0$$ indicates no reflection, while a $$\Gamma$$ of `1` or `-1` -represents total reflection with or without phase inversion. - -Here ($$Z_{0}$$) represents the reference impedance of the system which is -typically `50` $$\Omega$$. Maximum power transfer over the boundary from the -generator to the load is only satisfied when: - -$$ Z_{L} = Z_{R}^* $$ - -This expression is known as the conjugate match rule for maximum power transfer. -In most practical `RF` systems $$Z_{L} \neq Z_{R}$$ and so a method of impedance -transformation is required to satisfy the conjugate match rule. - -Impedance transformation networks allow a $$Z_{L}$$ with both a real and imaginary -part to be transformed into another complex impedance using reactive components. -Reactive components do not dissipate real power unlike resistors which is why -resistors are rarely used in `RF` impedance matching and filter networks. - -The most basic type of impedance transformation network is known as the `LC` -network which consists of an inductor and capacitor. It can be used to transform -a complex load ($$R_{L}$$) to `50` $$\Omega$$. The figure below shows the basic -configuration of the `LC` impedance transformation network. - - - -In addition to the `LC` network's impedance transformation property, the `LC` -network can have a low-pass or high-pass response depending on the shunt element -($$jB$$). If it is capacitive then the `LC` network will have a low-pass response or -a high-pass response if it is inductive. - -Typically the low pass configuration (with a shunt capacitor) is desired. - -It should be noted that the shunt element ($$jB$$) should be placed on the side -with the largest impedance. Therefore there are two possible configurations of -this network: - - - -So that type `1` is used when $$R_{L} > R_{S}$$ and type `2` is used when $$R_{L} < -R_{S}$$. Here $$Z_{S}$$ represents $$Z_{0}$$ the system reference impedance $$(50 -\Omega)$$. - -The design procedure for a type `1` `LC` network is as follows. First we evaluate -the input impedance ($$Z_{in}$$) looking into the matching network. - - - -We start by defining a few variables. Let: - -$$ Z_{L} = R_{L} + jX_{L} $$ - -$$ Z_{S} = Z_{0} = 50 \Omega $$ - -$$ Z_{in} = jX + \frac{1}{(jB)^{-1} + (Z_{L})^{-1}} $$ - -Matching conditions are met when $$Z_{in} = Z_{S} = Z_{0}$$. - -The equation above can be simplified and separated into real and imaginary -parts: - -$$ B(X + X_{L}) = -(Z_{0}R_{L}-XX_{L}) $$ - -$$ B(R_{L} - Z_{0}) = Z_{0}X_{L} - R_{L}X $$ - -`B` can then be solved using the following equation: - -$$ B = -\frac{R_{L}^2+X_{L}^2}{X_{L} + \sqrt{\frac{R_{L}}{Z_{0}}} \sqrt{R_{L}^2 + X_{L}^2 - Z_{0}R_{L}}} $$ - -Once `B` is obtained, X may be found by rearranging for `X`: - -$$ X = \frac{B(R_{L} - Z_{0}) - Z_{0}X_{L}}{-R_{L}} $$ - -The figure below depicts the second variant of the `LC` matching network. - - - -Let: - -$$ Z_{L} = R_{L} + jX_{L} $$ - -$$ Z_{S} = Z_{0} = 50 \Omega $$ - -$$ Z_{in} = \frac{1}{(jB)^{-1} + (Z_{L} + jX)^{-1}} $$ - -Matching conditions are met when $$Z_{in} = Z_{S} = Z_{0}$$. - -The equation above can be simplified and separated into real and imaginary -parts: - -$$ B(X_{L} + X) = -Z_{0}R_{L} $$ - -$$ B(Z_{0} - R_{L}) = -Z_{0}(X_{L}+X) $$ - -Again, B can then be solved using the following equation: - -$$ B = -Z_{0}\sqrt{\frac{R_{L}}{Z_{0}- R_{L}}} $$ - -Again, `X` may be found by rearranging for $$(X_{L} + X)$$ and substituting to -yield: - -$$ X = \sqrt{R_{L}(Z_{0} - R_{L})} - X_{L} $$ - -For both `LC` circuit types it is assumed that $$jB$$ represents a capacitive -element and $$jX$$ represents an inductive element so that a low-pass response is -obtained. - -Matching networks with more than two reactive elements also exist. These include -the $$\pi$$-section and `T-section` matching networks that contain `3` reactive -elements each. The figure below depicts the $$\pi$$-section network. - - - -The $$\pi$$-section network is made up of a type `2` `LC` matching network in cascade -with a type 1 `LC` matching network. The central element $$jX$$ is the sum of the -inductive reactance ($$jX$$) of each `LC` matching section, which is combined into a -single reactance. - -A virtual load resistance $$R_{x}$$ is interposed in-between the two `LC` matching -networks. The goal of the first `LC` matching network is to then match the source -$$Z_{S}$$ to $$R_{x}$$ while the second `LC` matching network matches $$R_{x}$$ to -$$Z_{L}$$. - -The value of $$R_{x}$$ is chosen according to the desired `Q-factor` and must be -smaller than $$R_{L}$$ and $$R_{S}$$. The `Q-factor` of a matching network describes -how well power is transferred from source to load as you deviate from the -designed center frequency of the matching network ($$f_{0}$$). - -Is it defined as follows: - -$$ Q = \frac{f_{0}}{B} $$ - -Here $$f_{0}$$ represents the center frequency of the matching network and B -represents the total bandwidth over which no greater than `3dB` of power is lost -from source to load. - -A high `Q-factor` is often desirable for a narrowband matching network. It should -be mentioned that the `Q-factor` cannot be controlled with a simple 2 element `LC` -matching network (which id determined by $$R_{L}$$ and $$R_{S}$$). This is one of -the advantages of the $$\pi$$-section matching network. - -The `Q-factor` for the $$\pi$$-section filter is given by: - -$$ Q_{\pi} = \sqrt{\frac{\max(R_{S}, R_{L})}{R_{x}} - 1} $$ - -Here `max()` is a function that returns the maximum of two values. Hence the -`Q-factor` of a $$\pi$$-section matching network will be determined by the `LC` -matching section with the highest `Q-factor`. - -# Electromagnetic Transducers - -Once the necessary `RF` power has been generated and transmitted over various -transmission lines and matching networks it then becomes necessary to convert -this `RF` power into electromagnetic waves which can start propagating through -free space to reach a receiver. For this purpose we use an electromagnetic -transducer known as an antenna. - -An antenna can be also be thought of as an impedance transformation network that -matches an `RF` circuit (`50` $$\Omega$$ typical) to free space (`377` $$\Omega$$). - -An antenna can be as simple as a piece of wire connected to an `RF` output port -but the efficiency of the antenna in this case would be very low. The two most -common types of antenna's are the `monopole` and `dipole` antenna (shown below). - - - -The `monopole` antenna consists of a `quarter-wave` length ($$\lambda/4$$) of wire of -length $$L$$ which is connected to the 'hot' `RF` input terminal and a infinitely -large `RF` ground plane conductor which is connected to electrical ground. The -'hot' and `RF` ground elements are electrically separated from each other. - -Most practical `HF` and `VHF` `monopole` antennas are shorter than a quarter -wavelength due to size constraints and are therefore modelled as electrically -small `monopoles` ($$L \leq (1/8)\lambda$$) from this point forward. - -An electrically small `monopole` antenna can be modelled as a series circuit with -the elements shown in the image below. - - - -$$L_{a}$$ represents the antenna conductor inductance. This is the parasitic -inductance of the active element of the antenna which is just a wire made out of -a material such as copper with a length and diameter. This value is usually very -small and can be neglected. - -The reactance of an electrically short `monopole` ($$L \leq (1/8)\lambda$$) is -represented by $$X_{a}$$ and can be calculated as follows: - -$$ X_{a} = 60(1 - \ln{(\frac{L}{a})})\cot{(2\pi\frac{L}{\lambda})}j \Omega $$ - -This equation originally appears in the "Antenna Engineering Handbook", Third -Edition by `Richard C. Johnson`. - -From the equation above it can be seen that the reactance of an electrically -short `monopole` is primarily capacitive. - -The radius of the wire (active element) in meters is given by $$a$$ and the -operational wavelength is given by $$\lambda$$. The operational wavelength can be -calculated by the transmit frequency ($$f_{t}$$) and the speed of light in a -vacuum ($$c$$): - -$$ \lambda = \frac{c}{f_{t}} $$ - -The loss resistance $$r_{a}$$ is the effective ac resistance of the antenna active -element due to the skin effect. The skin effect is a phenomenon whereby `RF` -current tends to flow near the surface of the conductor as the frequency, and as -a consequence, magnetic field strength at the center of the conductor increases. - -The skin depth is given by: - -$$ \delta = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi f_{t} \mu_{0} \sigma}} $$ - -$$\sigma$$ is the conductivity of the active element's composite material (copper) -while $$\mu_{0}$$ is the permeability constant. Once $$\sigma$$ is computed the real -ac resistance can be found as follows: - -$$ r_{a} = \frac{L}{2\pi a \delta \sigma} $$ - -At `VHF` the loss resistance $$r_{a}$$ is also very small and can typically be -neglected. - -The radiation resistance $$r_{R}$$ of an electrically small monopole ($$L \leq -(1/8)\lambda$$) is the effective real resistance that represents the power that -is radiated away from the antenna as electromagnetic waves. For an electrically -short `monopole`, radiation resistance is given by the equation below: - -$$ r_{R} = 40 \pi^2(\frac{L}{\lambda})^2 \Omega $$ - -$$r_{G}$$ represents the losses in the `RF` ground plane and this parameter is -usually neglected. A stable `RF` ground plane is essential for an antenna to -function correctly. An antenna ground plane serves as an `RF` return path for `AC` -displacement current. - -For a `monopole` the ground plane also serves the function of mirroring the active -radiation element to form the second half of the antenna. This derivation is -obtained using image theory and is beyond the scope of this journal entry. - -# S-Parameters - -Most passive `RF` circuits such as filters, matching networks, etc are linear. -That is their output voltage, current and power relationships are derived from a -system of linear equations. Some active devices such as `class-A` `small-signal` -amplifiers are also linear. - -Scattering parameters or `S-parameters` can be used to model the behaviour of -these `linear` `RF` networks when stimulated by a steady-state signal. - - - -The image above depicts a `DUT` 'black box' which we use to derive the scattering -parameters. The network has `2` distinct ports (`port 1`, `port 2`) and 4 scattering -parameters: $$S_{11}, S_{12}$$ and $$S_{21}, S_{22}$$. The scattering parameters are -complex values with both a real and imaginary part. - -We define each scattering parameter in terms of two voltage waves at the input -(`port 1`) and output (`port 2`). Let $$a_{1}, b_{1}$$ represents the incident and -reflected voltage waves at `port 1` while $$a_{2}, b_{2}$$ represent the incident -and reflected voltage waves at `port 2`. - -The S-parameters can then be defined as follows: - -$$ S_{11} = \frac{b_{1}}{a_{1}} = \frac{V_{1}^-}{V_{1}^+}, S_{12} = -\frac{b_{1}}{a_{2}} = \frac{V_{1}^-}{V_{2}^+} $$ - -$$ S_{21} = \frac{b_{2}}{a_{1}} = \frac{V_{2}^-}{V_{1}^+}, S_{22} = -\frac{b_{2}}{a_{2}} = \frac{V_{2}^-}{V_{2}^+} $$ - -It should be mentioned at this point that s-parameters can also be defined in -terms of 'power waves' by considering the complex input impedance of the `DUT`. -However the voltage wave definition is the most popular. - -A system of linear equations can then be derived for $$b_{1}$$ and $$b_{2}$$: - -$$ b_{1} = S_{11}a_{1} + S_{12}a_{2} $$ - -$$ b_{2} = S_{21}a_{1} + S_{22}a_{2} $$ - -Which can be expressed in terms of the `S-parameter` matrix: - -$$ \begin{bmatrix} b_{1} \\ -b_{2} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} S_{11} S_{12} \\ -S_{21} S_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a_{1} \\ -a_{2} \end{pmatrix} $$ - -There are various useful definitions that can be derived from the scattering -parameters. $$S_{21}$$ and $$S_{11}$$ are the most commonly used scattering -paramters. - -The first useful definition is the logarithmic power gain of the network in `dB` -($$G_{p}$$) which can be expressed in terms of $$|S_{21}|$$: - -$$ G_{p} = 20\log_{10}|S_{21}| $$ - -$$S_{11}$$ is related to the input reflection coefficient $$\Gamma_{in}$$ and can be -used to obtain the input impedance of the network $$Z_{in}$$: - -$$ S_{11} = \Gamma_{in} $$ - -$$ Z_{in} = Z_{0} \frac{1+S_{11}}{1-S_{11}} $$ - -The ratio of reflected ($$P_{ref}$$) and incident power ($$P_{inc}$$) at `port 1` is -given by: - -$$ \frac{P_{ref}}{P_{inc}} = |\Gamma_{in}|^2 $$ - -Another useful definition is the input (`port 1`) return loss $$RL_{in}$$: - -$$ RL_{in} = -20\log_{10}(|S_{11}|) $$ - -From the above formula it can be seen that return loss is typically a positive -number (since $$|S11| < 0$$), however sometimes it is quoted as a negative number -in which case the data is referring to the `log` magnitude of $$S_{11}$$ directly -($$-RL_{in}$$), not the actual return loss which is positive as mentioned. - -Return loss for ($$S_{11}$$) is a measure of how well matched `port 1` of the -network is to the reference impedance. A return loss greater than `10dB` is -usually desirable for a good match. - -Another measure of how well matched a network is to the reference impedance is -called `VSWR` (voltage standing wave ratio). The `VSWR` of `port 1` ($$s_{in}$$) is -defined by: - -$$ s_{in} = \frac{1+|S_{11}|}{1-|S_{11}|} $$ - -`VSWR` is typically used to measure the matching conditions of antennas. A -($$s_{in} < 2$$) is generally considered suitable for most antenna applications. - -A `VNA` (Vector Network Analyzer) is an instrument that is used to measure -`S-parameters`. Most affordable commercial `VNA's` are `2-port` `1-path` devices, i.e -they only measure $$S_{11}$$ and $$S_{21}$$ and the `DUT` must therefore be reversed -to obtain $$S_{22}$$ and $$S_{12}$$. - -The input and output impedance obtained for $$S_{11}$$ and $$S_{22}$$ can also be -represented in graphical form as a smith chart. A `smith chart` is a real and -imaginary chart where the imaginary (`y-axis`) axis has been bent around the -`x-axis`. It can be used to plot any value of complex impedance. An example of the -`smith chart` is shown in the figure below. - -The top half of the smith chart represent inductive reactance while the bottom -half represents capacitive reactance. The circles passing through the `x-axis` are -known as constant resistance circles where the left most point on the real axis -of the smith chart represents a short circuit (`SC`) while the rightmost point -represents an open circuit (`OC`). - -For an ideal `50` $$\Omega$$ match there should be a single point in the middle of -the smith chart. - -{:height="300px"} - -# Harmonic Balance - -`RF` power amplifier's are `large-signal` non-linear devices. - -At this point a distinction is required between small signal and large signal -amplifiers. For `small-signal` amplifiers the input and output power is typically -small and these devices typically operate in their `linear` region. - -`Large-signal`, `class AB`, `B` and `C` devices typically operate with large input and -output power and their response is strongly `non-linear` due to the class of -operation. Therefore for power amplifier classes other than `class A`, -`S-parameters` cannot be used reliably in the design of `RF` power amplifiers. - -Rather a designer relies on vendor supplied `non-linear` software models of the -power amplifier transistor and typically uses a `non-linear` frequency domain -analysis technique such as the harmonic balance method (`HBM`) to characterise the -power amplifier's performance. - -`Harmonic balance` is a frequency domain technique used to calculate the steady -state response of a non-linear circuit. `HBM` can be defined in multiple ways, -however in this case let us demonstrate `HBM` through an example circuit. - -Given a circuit with $$N$$ nodes, let vector $$v$$ represent the respective node -voltages. For ease of representation we model a circuit with capacitors and -voltage controlled resistors. Then applying `KCL` (Kirchoff's Current Law) to the -circuit yields the following systems of equations: - -$$ f(v,t) = i(v(t)) + \frac{d}{dt}q(v(t)) + \int_{-\infty}^t{y(t-\tau)v(\tau)} + -i_{s}(t) = 0 $$ - -We let $$q$$ and $$i$$ represent the sum of the charges and currents entering the -nodes due to the non-linearities. $$y$$ is the impulse response matrix of the -circuit with all non-linearities removed while $$i_{s}$$ represents the external -source currents. - -We then convert equation above into the frequency domain: - -$$ F(V) = I(V) + ZQ(V) + YV + I_{s} = 0 $$ - -Here $$Z$$ represents a matrix with frequency coefficients representing the -differentiation step. The convolution integral in the equation above maps to `YV` -as shown where `Y` is the admittance matrix for the `linear` portion of the circuit. - -`V` then contains the fourier coefficients of the voltage at each $$N$$ nodes at -every harmonic. This process is merely nothing more than `KCL` in the frequency -domain for `non-linear` circuits. - -# Lumped and Distributed Element Networks - -As mentioned above, as the size of a circuit element starts to approach a -fraction (typically `1/10`) of the wavelength of the highest `RF` signal frequency, -the lumped element approximation for the circuit element no longer holds. In -these cases lumped or discrete components cannot be used and so a distributed -element/model must be utilized. - -Traditionally the use of lumped element components at `RF` frequencies is most -common below around `500 MHz`. Above `500 MHz` these lumped circuit -elements become more difficult to design with. - -# Classes Of Operation - -Depending on the `DC` operating point of the power transistor, different values of -efficiency and output power can be obtained for the same input power. Efficiency -is generally considered the most important design parameter for an `RF` power -amplifier. - -In the `class-A` configuration the transistor is biased such that the quiescent -drain current is equal to the peak amplitude of the current expected through the -load. This allows for a symmetrical voltage and current swing at the output and -the transistor conducts for the full `360` degrees of the input waveform. - -The advantages of this configuration are excellent linearity and gain at the -expense of reduced efficiency. A `class-A` power amplifier with an inductively -loaded drain has a maximum theoretical efficiency of `50%`. - -`Class-B` power amplifiers aim to achieve greater efficiency by only conducting -for half of the input drive cycle (`180` degrees). `Class-B` power amplifiers have a -maximum theoretical efficiency of `75%` and the transsitor is biased at cutoff. -Again `class-B` `PA's` can be placed in a single-ended configuration or push-pull. -The advantage of `class-B` are increased efficiency at the expense of decreased -linearity. - -A compromise is thus needed between `class A` and `class B` such that we have -sufficient linearity at a reasonable efficiency. A `class-AB` power amplifier is a -solution to this problem. - -In the `class-AB` mode of operation the transistor is biased with a quiescent -drain current slightly to moderately above cutoff, depending on the linearity -requirements. This improves the linearity of the power amplifier while typically -maintaining an efficiency of `50%` to `70%` in practice. `Class-AB` power -amplifier's have a conduction angle between `180` and `360` degrees. - -The `single-ended`, `class-AB` mode of operation is therefore a popular choice -amongst designers. - -# Stability Analysis - -`RF` power -amplifier's are inherently unstable devices which often require some form of -stabilization to operate correctly. - -Amplifier instability is usually caused by some type of gain and feedback -mechanism. In `MOSFET` transistor's the feedback mechanism is typically due to the -gate to drain capacitance that couples a portion of the output back into the -input and vice versa. This effect often manifests as unwanted oscillation at -either the input and output of the PA. - -Small signal parameters (such as `S-parameters`) are typically used to -characterize stability of `RF` power amplifier's even though these are `non-linear` -devices. This is because small signal models can still provide useful insights -into the design of a `PA` without requiring complex non-linear calculations. -Typically the operation of a `PA` is linearized around an operating point. - -There are various stability factors available to a designer and an amplifier may -be conditionally stable or unconditionally stable. If an amplifier is -conditionally stable then there exists a load and source impedance that causes -the amplifier to oscillate. Therefore unconditional stability is usually -desired. - -The most common stability factor in use is the `Rollet` stability factor ($$K$$) -which is defined as follows: - -$$ K = \frac{1 - |S_{11}|^2 - |S_{22}|^2 + | \Delta |^2}{2|S_{12}S_{21}|} $$ - -Here $$\|\Delta\|$$ is defined as the scattering-matrix determinant: - -$$ | \Delta | = |S_{11}S_{22} - S_{21}S_{12}| $$ - -We define three more stability Criterion in terms of $$\Delta, B_{1}$$ and -$$B_{2}$$: - -$$ B_{1} = 1 + |S_{11}|^2 - |S_{22}|^2 - |\Delta|^2 $$ - -$$ B_{2} = 1 + |S_{22}|^2 - |S_{11}|^2 - |\Delta|^2 $$ - -In order for an amplifier to be conditionally stable we require the -following conditions: - -$$ K \ge 1 $$ - -$$ \Delta < 1 $$ - -$$ B_{1} > 0, B_{2} > 0 $$ - -# Efficiency -The most common measure of `RF` power amplifier efficiency is $$PAE$$ -(power added efficiency) and is defined as follows: - -$$ PAE = \frac{P_{out} - P_{in}}{P_{DC}} $$ - -Here $$P_{in}$$ represents the `RF` input power from the source, $$P_{out}$$ -represents `RF` power delivered to the load and $$P_{DC}$$ represents the total `DC` -power. - -# P1dB Compression Point - -The `P1dB` point is defined as the output power level at which -the gain of an amplifier decreases by `1 dB` from its nominal value which -indicates the onset of gain non-linearity. - -Most amplifier's start to compress approximately `5` to `10 dB` below their `P1dB` -point. - -The `P1dB` point indicates that power amplifier's have a linear and non-linear -region of power gain. - -# Load Pull - -`Load-pull` is an empirical `RF` `PA` design technique in which the -reflection coefficient or impedance presented to the drain of a `RF` power -transistor is varied by an electrical or mechanical impedance tuner to any -arbitrary value. The technique is traditionally used to determine the optimum -load impedance to present to an `RF` power amplifier for maximum output power. - -Once the optimum load impedance is determined the synthesis of matching networks -can then take place. `Load-pull` tuners are expensive devices and are therefore -typically out of the reach of most students or experimenters. - -In the case where a physical `load-pull` tuner is not available and a `non-linear` -model for the chosen `RF` power transistor exists, then a simulated `load-pull` can -be performed. - -# LC Filtering - -As `non-linear` devices, power amplifiers typically produce -harmonic frequency content that must be filtered out in order to comply with -regulatory standards on spurious emissions. `LC` networks can be constructed with -varying number of elements (poles) in order to achieve a specific roll-off in -the stop-band. - -Two types of filter response are commonly used in `RF` circuit design, these are -the `Chebyshev` and `Butterworth` responses. `Chebyshev` `LC` filters typically have a -steeper roll-off but suffer from passband ripple. - -`Butterworth` `LC` filters typically have a flat response in the passband with a -gradual roll-off in the stop band. These types of filters can be designed -manually using filter constants or using `RF` design software such as `Matlab` (`RF -Toolbox`) and typically an optimization algorithm. We typically optomize for -either stopband attenuation or input impedance. - -That concludes this journal entry! I have just touched on some basic principles that -might help with understanding more advanced concepts. - -# Signature - -``` -+---------------------------------------+ -| .-. .-. .-. | -| / \ / \ / \ + | -| \ / \ / \ / | -| "_" "_" "_" | -| | -| _ _ _ _ _ _ ___ ___ _ _ | -| | | | | | | \| | /_\ | _ \ / __| || | | -| | |_| |_| | .` |/ _ \| /_\__ \ __ | | -| |____\___/|_|\_/_/ \_\_|_(_)___/_||_| | -| | -| | -| Lunar RF Labs | -| https://lunar.sh | -| | -| Research Laboratories | -| Copyright (C) 2022-2024 | -| | -+---------------------------------------+ -``` |