1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

|

---

layout: post

title: RF Circuit and Power Amplifier Design Basics

author: Dylan Müller

---

> A short primer on some of the basic concepts related to `RF` circuit

> and `RF` power amplifier design.

1. [Average Power](#average-power)

2. [Transmission Lines](#transmission-lines)

3. [Impedance Matching](#impedance-matching)

4. [Electromagnetic Transducers](#electromagnetic-transducers)

5. [S-Parameters](#s-parameters)

6. [Harmonic Balance](#harmonic-balance)

7. [Lumped and Distributed Element Networks](#lumped-and-distributed-element-networks)

8. [Classes Of Operation](#classes-of-operation)

9. [Stability Analysis](#stability-analysis)

10. [Efficiency](#efficiency)

11. [P1dB Compression Point](#p1db-compression-point)

12. [Load Pull](#load-pull)

13. [LC Filtering](#lc-filtering)

# Foreword

The aim of this journal entry is to review some basic technical concepts

pertaining to general `RF` circuit design and modelling as well as `RF` power

amplifier design.

`RF` circuit design is typically not covered in detail at an undergraduate level

and the author hopes that this journal entry will provide some useful

information to readers not familiar with the subject.

# Average Power

In order to be successful in `RF` power amplifier design, it is necessary to

understand `AC` power from both a frequency and time domain perspective.

In the frequency-domain, complex `AC` power ($$S$$) is given by:

$$ S = \overline{V}.\overline{I}^* $$

Where $$\overline{V}$$ and $$\overline{I}$$ are the voltage and current phasors. In

`RF` power amplifier design we are typically concerned with maximizing the real

component of complex power $$\Re(S)$$ which represents power dissipated in a load

such as an antenna (modelled by it's radiation resistance). The imaginary part

of $$S$$ represents reactive power which does not perform any useful work.

Average real power ($$P_{avg}$$) is the industry standard measure of power for `RF`

and `microwave` systems and is measured in the `SI` units of `watts (W)`. Average

power over total time ($$T$$) for a continuous-wave (`CW`) signal is defined by the

following time-domain integral:

$$ P_{avg} = \frac{1}{T} \int\limits_0^T v(t).i(t) dt $$

The terms $$v(t)$$ and $$i(t)$$ can then be expanded:

$$ v(t) = v_{p}sin(2\pi ft), i(t) = i_{p}sin(2\pi ft + \theta) $$

Here $$\theta$$ represents the phase angle between $$i(t)$$ and $$v(t)$$ and ($$v_{p}$$)

and ($$i_{p}$$) represent the peak values of the voltage and current waveforms.

It can be shown that for purely sinusoidal voltage and current waveforms:

$$ P_{avg} = \frac{1}{2}v_{p}i_{p}cos(\theta) $$

Hence maximum real power is obtained when the current and voltage waveforms are

in phase. $$cos (\theta)$$ is commonly referred to as the power factor and this

constant relates real power to apparent power $$\|S\|$$. Apparent power is the

total complex power available to a particular load.

In practice average real power is specified in terms of decibels referenced to `1`

`milliwatt (mW)` ($$dBm$$):

$$ dBm(P) = 10\log_{10}(\frac{P}{1mW}) $$

While relative power is measured in decibels ($$dB$$):

$$ dB(P) = 10\log_{10}(\frac{P}{P_{ref}}) $$

## Transmission Lines

Traditional lumped circuit theory is only applicable to low frequency circuits

as it assumes that wires are lossless with negligible electrical length.

Electrical length is usually measured in terms of multiples of the wavelength

($$\lambda$$) of the highest frequency signal that is conducted over the line.

As a rule of thumb, when the length of a wire is greater or equal to

$$\lambda/10$$, the voltage and current in the wire as a function of position

along the wire will no longer be constant with time and wave-like behaviour such

as reflection and standing waves start becoming important. In these cases

utilizing a distributed model, such as the transmission line, often becomes

necessary.

Let $${u}$$ and $${i}$$ represent the voltage and current along the transmission line as

a function of position and time:

$$ u = u(x,t), i = i(x,t) $$

Then at distance $${x+dx}$$ voltage and current can be expressed with a taylor

series expansion:

$$ u(x + dx) = u(x,t) + \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} dx $$

$$ i(x + dx) = i(x,t) + \frac{\partial i}{\partial x} dx $$

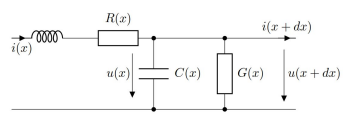

A segment of a traditional transmission line is shown in the figure below. It

consists of a series distributed resistance $$R(x)$$, inductance $$L(x)$$ as well as

segment capacitance $$C(x)$$ and conductance $$G(x)$$. A transmission line is

thought of as a continuous series of these segments.

It can be shown that the equations that describe changes in the voltage and

current on the line is given by:

$$ \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} dx = -Ri - L \frac{\partial i}{\partial t} $$

$$ \frac{\partial i}{\partial x} dx = -Gu - C \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} $$

The equations above are known as the telegrapher's equations. These two

equations can be combined to produce two partial differential equations with one

isolated variable each ($${u}$$ or $${i}$$).

$$u$$ and $$i$$ are related by the characteristic impedance ($$Z_{0}$$) of the

transmission line which can be derived from the telegraphers equations:

$$ Z_{0} = \frac{V^+(x)}{I^+(x)} = \sqrt{\frac{R(x)+j\omega L(x)}{G(x)+j\omega

C(x)}} $$

For most transmission lines dielectric and conductor losses are low, so we

assume:

$$ R(x) \ll j\omega L(x), G(x) \ll j\omega C(x) $$

As a result the equation above simplifies to:

$$ Z_{0} = \sqrt{\frac{L(x)}{C(x)}} $$

It is worth noting that characteristic impedance $$Z_{0}$$ of a transmission line

only has an effect at `RF` frequencies. It is not possible to measure the

characteristic impedance of a transmission line directly with a multimeter

because resistance (ohms law) and characteristic impedance (electromagnetic

property) are not the same concept.

Examples of transmission lines include coaxial cable and microstrip line.

Transmission lines typically have a characteristic impedance of `50` $$\Omega$$ in

`RF` systems and are used to carry `RF` signals from one point in a circuit to

another with minimal losses.

# Impedance Matching

It is often said that impedance matching is what truly differentiates `RF` circuit

design from low frequency circuit design. Indeed, it is one of the most common

tasks for an `RF` designer.

`RF` signals travelling along a transmission line can be thought of as

electromagnetic power waves. Power waves are a hypothetical construct, one of

the many possible linear transformations of voltage and current.

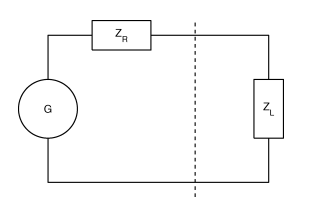

The figure below shows a typical `RF circuit` consisting of a `RF` power source

($$G$$) with an impedance of ($$Z_{R}$$) and a load with an impedance of $$Z_{L}$$.

The interface of the generator and load impedance is indicated by the dotted

line.

It is at this interface that we experience reflection of the power wave (back to

the generator) when $$Z_{R} \neq Z_{L}$$. If the impedance of the generator and

load were equal then no reflection occurs.

In general, the goal of an `RF` system is to transfer `RF` power as efficiently from

one point to another with minimal reflections. The degree of an electromagnetic

power wave reflected (at the boundary) is determined by the reflection

coefficient ($$\Gamma$$):

$$ \Gamma_{L} = \frac{Z_{L} - Z_{0}}{Z_{L}+Z_{0}} $$

A $$\Gamma$$ of $$0$$ indicates no reflection, while a $$\Gamma$$ of `1` or `-1`

represents total reflection with or without phase inversion.

Here ($$Z_{0}$$) represents the reference impedance of the system which is

typically `50` $$\Omega$$. Maximum power transfer over the boundary from the

generator to the load is only satisfied when:

$$ Z_{L} = Z_{R}^* $$

This expression is known as the conjugate match rule for maximum power transfer.

In most practical `RF` systems $$Z_{L} \neq Z_{R}$$ and so a method of impedance

transformation is required to satisfy the conjugate match rule.

Impedance transformation networks allow a $$Z_{L}$$ with both a real and imaginary

part to be transformed into another complex impedance using reactive components.

Reactive components do not dissipate real power unlike resistors which is why

resistors are rarely used in `RF` impedance matching and filter networks.

The most basic type of impedance transformation network is known as the `LC`

network which consists of an inductor and capacitor. It can be used to transform

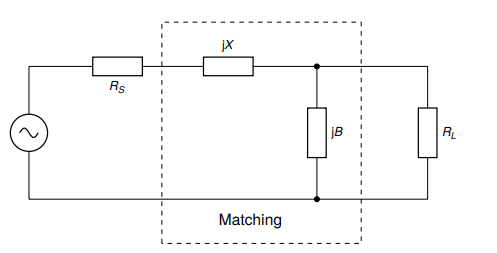

a complex load ($$R_{L}$$) to `50` $$\Omega$$. The figure below shows the basic

configuration of the `LC` impedance transformation network.

In addition to the `LC` network's impedance transformation property, the `LC`

network can have a low-pass or high-pass response depending on the shunt element

($$jB$$). If it is capacitive then the `LC` network will have a low-pass response or

a high-pass response if it is inductive.

Typically the low pass configuration (with a shunt capacitor) is desired.

It should be noted that the shunt element ($$jB$$) should be placed on the side

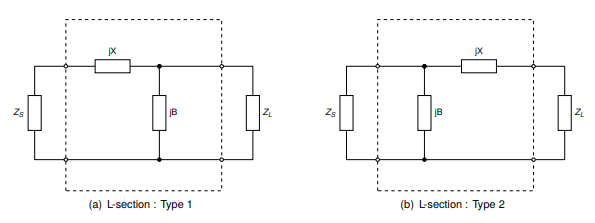

with the largest impedance. Therefore there are two possible configurations of

this network:

So that type `1` is used when $$R_{L} > R_{S}$$ and type `2` is used when $$R_{L} <

R_{S}$$. Here $$Z_{S}$$ represents $$Z_{0}$$ the system reference impedance $$(50

\Omega)$$.

The design procedure for a type `1` `LC` network is as follows. First we evaluate

the input impedance ($$Z_{in}$$) looking into the matching network.

We start by defining a few variables. Let:

$$ Z_{L} = R_{L} + jX_{L} $$

$$ Z_{S} = Z_{0} = 50 \Omega $$

$$ Z_{in} = jX + \frac{1}{(jB)^{-1} + (Z_{L})^{-1}} $$

Matching conditions are met when $$Z_{in} = Z_{S} = Z_{0}$$.

The equation above can be simplified and separated into real and imaginary

parts:

$$ B(X + X_{L}) = -(Z_{0}R_{L}-XX_{L}) $$

$$ B(R_{L} - Z_{0}) = Z_{0}X_{L} - R_{L}X $$

`B` can then be solved using the following equation:

$$ B = -\frac{R_{L}^2+X_{L}^2}{X_{L} + \sqrt{\frac{R_{L}}{Z_{0}}} \sqrt{R_{L}^2 + X_{L}^2 - Z_{0}R_{L}}} $$

Once `B` is obtained, X may be found by rearranging for `X`:

$$ X = \frac{B(R_{L} - Z_{0}) - Z_{0}X_{L}}{-R_{L}} $$

The figure below depicts the second variant of the `LC` matching network.

Let:

$$ Z_{L} = R_{L} + jX_{L} $$

$$ Z_{S} = Z_{0} = 50 \Omega $$

$$ Z_{in} = \frac{1}{(jB)^{-1} + (Z_{L} + jX)^{-1}} $$

Matching conditions are met when $$Z_{in} = Z_{S} = Z_{0}$$.

The equation above can be simplified and separated into real and imaginary

parts:

$$ B(X_{L} + X) = -Z_{0}R_{L} $$

$$ B(Z_{0} - R_{L}) = -Z_{0}(X_{L}+X) $$

Again, B can then be solved using the following equation:

$$ B = -Z_{0}\sqrt{\frac{R_{L}}{Z_{0}- R_{L}}} $$

Again, `X` may be found by rearranging for $$(X_{L} + X)$$ and substituting to

yield:

$$ X = \sqrt{R_{L}(Z_{0} - R_{L})} - X_{L} $$

For both `LC` circuit types it is assumed that $$jB$$ represents a capacitive

element and $$jX$$ represents an inductive element so that a low-pass response is

obtained.

Matching networks with more than two reactive elements also exist. These include

the $$\pi$$-section and `T-section` matching networks that contain `3` reactive

elements each. The figure below depicts the $$\pi$$-section network.

The $$\pi$$-section network is made up of a type `2` `LC` matching network in cascade

with a type 1 `LC` matching network. The central element $$jX$$ is the sum of the

inductive reactance ($$jX$$) of each `LC` matching section, which is combined into a

single reactance.

A virtual load resistance $$R_{x}$$ is interposed in-between the two `LC` matching

networks. The goal of the first `LC` matching network is to then match the source

$$Z_{S}$$ to $$R_{x}$$ while the second `LC` matching network matches $$R_{x}$$ to

$$Z_{L}$$.

The value of $$R_{x}$$ is chosen according to the desired `Q-factor` and must be

smaller than $$R_{L}$$ and $$R_{S}$$. The `Q-factor` of a matching network describes

how well power is transferred from source to load as you deviate from the

designed center frequency of the matching network ($$f_{0}$$).

Is it defined as follows:

$$ Q = \frac{f_{0}}{B} $$

Here $$f_{0}$$ represents the center frequency of the matching network and B

represents the total bandwidth over which no greater than `3dB` of power is lost

from source to load.

A high `Q-factor` is often desirable for a narrowband matching network. It should

be mentioned that the `Q-factor` cannot be controlled with a simple 2 element `LC`

matching network (which id determined by $$R_{L}$$ and $$R_{S}$$). This is one of

the advantages of the $$\pi$$-section matching network.

The `Q-factor` for the $$\pi$$-section filter is given by:

$$ Q_{\pi} = \sqrt{\frac{\max(R_{S}, R_{L})}{R_{x}} - 1} $$

Here `max()` is a function that returns the maximum of two values. Hence the

`Q-factor` of a $$\pi$$-section matching network will be determined by the `LC`

matching section with the highest `Q-factor`.

# Electromagnetic Transducers

Once the necessary `RF` power has been generated and transmitted over various

transmission lines and matching networks it then becomes necessary to convert

this `RF` power into electromagnetic waves which can start propagating through

free space to reach a receiver. For this purpose we use an electromagnetic

transducer known as an antenna.

An antenna can be also be thought of as an impedance transformation network that

matches an `RF` circuit (`50` $$\Omega$$ typical) to free space (`377` $$\Omega$$).

An antenna can be as simple as a piece of wire connected to an `RF` output port

but the efficiency of the antenna in this case would be very low. The two most

common types of antenna's are the `monopole` and `dipole` antenna (shown below).

The `monopole` antenna consists of a `quarter-wave` length ($$\lambda/4$$) of wire of

length $$L$$ which is connected to the 'hot' `RF` input terminal and a infinitely

large `RF` ground plane conductor which is connected to electrical ground. The

'hot' and `RF` ground elements are electrically separated from each other.

Most practical `HF` and `VHF` `monopole` antennas are shorter than a quarter

wavelength due to size constraints and are therefore modelled as electrically

small `monopoles` ($$L \leq (1/8)\lambda$$) from this point forward.

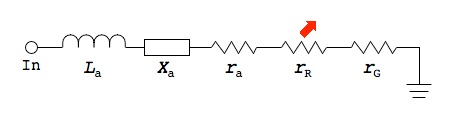

An electrically small `monopole` antenna can be modelled as a series circuit with

the elements shown in the image below.

$$L_{a}$$ represents the antenna conductor inductance. This is the parasitic

inductance of the active element of the antenna which is just a wire made out of

a material such as copper with a length and diameter. This value is usually very

small and can be neglected.

The reactance of an electrically short `monopole` ($$L \leq (1/8)\lambda$$) is

represented by $$X_{a}$$ and can be calculated as follows:

$$ X_{a} = 60(1 - \ln{(\frac{L}{a})})\cot{(2\pi\frac{L}{\lambda})}j \Omega $$

This equation originally appears in the "Antenna Engineering Handbook", Third

Edition by `Richard C. Johnson`.

From the equation above it can be seen that the reactance of an electrically

short `monopole` is primarily capacitive.

The radius of the wire (active element) in meters is given by $$a$$ and the

operational wavelength is given by $$\lambda$$. The operational wavelength can be

calculated by the transmit frequency ($$f_{t}$$) and the speed of light in a

vacuum ($$c$$):

$$ \lambda = \frac{c}{f_{t}} $$

The loss resistance $$r_{a}$$ is the effective ac resistance of the antenna active

element due to the skin effect. The skin effect is a phenomenon whereby `RF`

current tends to flow near the surface of the conductor as the frequency, and as

a consequence, magnetic field strength at the center of the conductor increases.

The skin depth is given by:

$$ \delta = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi f_{t} \mu_{0} \sigma}} $$

$$\sigma$$ is the conductivity of the active element's composite material (copper)

while $$\mu_{0}$$ is the permeability constant. Once $$\sigma$$ is computed the real

ac resistance can be found as follows:

$$ r_{a} = \frac{L}{2\pi a \delta \sigma} $$

At `VHF` the loss resistance $$r_{a}$$ is also very small and can typically be

neglected.

The radiation resistance $$r_{R}$$ of an electrically small monopole ($$L \leq

(1/8)\lambda$$) is the effective real resistance that represents the power that

is radiated away from the antenna as electromagnetic waves. For an electrically

short `monopole`, radiation resistance is given by the equation below:

$$ r_{R} = 40 \pi^2(\frac{L}{\lambda})^2 \Omega $$

$$r_{G}$$ represents the losses in the `RF` ground plane and this parameter is

usually neglected. A stable `RF` ground plane is essential for an antenna to

function correctly. An antenna ground plane serves as an `RF` return path for `AC`

displacement current.

For a `monopole` the ground plane also serves the function of mirroring the active

radiation element to form the second half of the antenna. This derivation is

obtained using image theory and is beyond the scope of this journal entry.

# S-Parameters

Most passive `RF` circuits such as filters, matching networks, etc are linear.

That is their output voltage, current and power relationships are derived from a

system of linear equations. Some active devices such as `class-A` `small-signal`

amplifiers are also linear.

Scattering parameters or `S-parameters` can be used to model the behaviour of

these `linear` `RF` networks when stimulated by a steady-state signal.

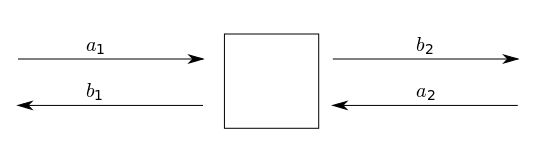

The image above depicts a `DUT` 'black box' which we use to derive the scattering

parameters. The network has `2` distinct ports (`port 1`, `port 2`) and 4 scattering

parameters: $$S_{11}, S_{12}$$ and $$S_{21}, S_{22}$$. The scattering parameters are

complex values with both a real and imaginary part.

We define each scattering parameter in terms of two voltage waves at the input

(`port 1`) and output (`port 2`). Let $$a_{1}, b_{1}$$ represents the incident and

reflected voltage waves at `port 1` while $$a_{2}, b_{2}$$ represent the incident

and reflected voltage waves at `port 2`.

The S-parameters can then be defined as follows:

$$ S_{11} = \frac{b_{1}}{a_{1}} = \frac{V_{1}^-}{V_{1}^+}, S_{12} =

\frac{b_{1}}{a_{2}} = \frac{V_{1}^-}{V_{2}^+} $$

$$ S_{21} = \frac{b_{2}}{a_{1}} = \frac{V_{2}^-}{V_{1}^+}, S_{22} =

\frac{b_{2}}{a_{2}} = \frac{V_{2}^-}{V_{2}^+} $$

It should be mentioned at this point that s-parameters can also be defined in

terms of 'power waves' by considering the complex input impedance of the `DUT`.

However the voltage wave definition is the most popular.

A system of linear equations can then be derived for $$b_{1}$$ and $$b_{2}$$:

$$ b_{1} = S_{11}a_{1} + S_{12}a_{2} $$

$$ b_{2} = S_{21}a_{1} + S_{22}a_{2} $$

Which can be expressed in terms of the `S-parameter` matrix:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} b_{1} \\

b_{2} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} S_{11} S_{12} \\

S_{21} S_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a_{1} \\

a_{2} \end{pmatrix} $$

There are various useful definitions that can be derived from the scattering

parameters. $$S_{21}$$ and $$S_{11}$$ are the most commonly used scattering

paramters.

The first useful definition is the logarithmic power gain of the network in `dB`

($$G_{p}$$) which can be expressed in terms of $$|S_{21}|$$:

$$ G_{p} = 20\log_{10}|S_{21}| $$

$$S_{11}$$ is related to the input reflection coefficient $$\Gamma_{in}$$ and can be

used to obtain the input impedance of the network $$Z_{in}$$:

$$ S_{11} = \Gamma_{in} $$

$$ Z_{in} = Z_{0} \frac{1+S_{11}}{1-S_{11}} $$

The ratio of reflected ($$P_{ref}$$) and incident power ($$P_{inc}$$) at `port 1` is

given by:

$$ \frac{P_{ref}}{P_{inc}} = |\Gamma_{in}|^2 $$

Another useful definition is the input (`port 1`) return loss $$RL_{in}$$:

$$ RL_{in} = -20\log_{10}(|S_{11}|) $$

From the above formula it can be seen that return loss is typically a positive

number (since $$|S11| < 0$$), however sometimes it is quoted as a negative number

in which case the data is referring to the `log` magnitude of $$S_{11}$$ directly

($$-RL_{in}$$), not the actual return loss which is positive as mentioned.

Return loss for ($$S_{11}$$) is a measure of how well matched `port 1` of the

network is to the reference impedance. A return loss greater than `10dB` is

usually desirable for a good match.

Another measure of how well matched a network is to the reference impedance is

called `VSWR` (voltage standing wave ratio). The `VSWR` of `port 1` ($$s_{in}$$) is

defined by:

$$ s_{in} = \frac{1+|S_{11}|}{1-|S_{11}|} $$

`VSWR` is typically used to measure the matching conditions of antennas. A

($$s_{in} < 2$$) is generally considered suitable for most antenna applications.

A `VNA` (Vector Network Analyzer) is an instrument that is used to measure

`S-parameters`. Most affordable commercial `VNA's` are `2-port` `1-path` devices, i.e

they only measure $$S_{11}$$ and $$S_{21}$$ and the `DUT` must therefore be reversed

to obtain $$S_{22}$$ and $$S_{12}$$.

The input and output impedance obtained for $$S_{11}$$ and $$S_{22}$$ can also be

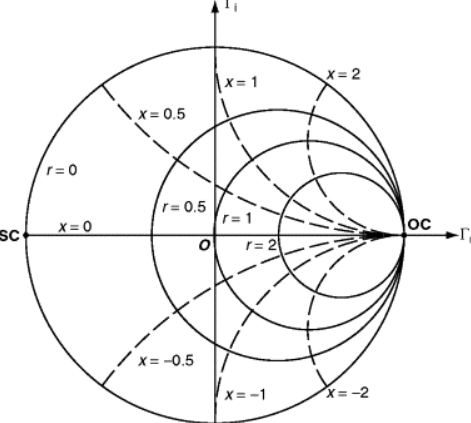

represented in graphical form as a smith chart. A `smith chart` is a real and

imaginary chart where the imaginary (`y-axis`) axis has been bent around the

`x-axis`. It can be used to plot any value of complex impedance. An example of the

`smith chart` is shown in the figure below.

The top half of the smith chart represent inductive reactance while the bottom

half represents capacitive reactance. The circles passing through the `x-axis` are

known as constant resistance circles where the left most point on the real axis

of the smith chart represents a short circuit (`SC`) while the rightmost point

represents an open circuit (`OC`).

For an ideal `50` $$\Omega$$ match there should be a single point in the middle of

the smith chart.

{:height="300px"}

# Harmonic Balance

`RF` power amplifier's are `large-signal` non-linear devices.

At this point a distinction is required between small signal and large signal

amplifiers. For `small-signal` amplifiers the input and output power is typically

small and these devices typically operate in their `linear` region.

`Large-signal`, `class AB`, `B` and `C` devices typically operate with large input and

output power and their response is strongly `non-linear` due to the class of

operation. Therefore for power amplifier classes other than `class A`,

`S-parameters` cannot be used reliably in the design of `RF` power amplifiers.

Rather a designer relies on vendor supplied `non-linear` software models of the

power amplifier transistor and typically uses a `non-linear` frequency domain

analysis technique such as the harmonic balance method (`HBM`) to characterise the

power amplifier's performance.

`Harmonic balance` is a frequency domain technique used to calculate the steady

state response of a non-linear circuit. `HBM` can be defined in multiple ways,

however in this case let us demonstrate `HBM` through an example circuit.

Given a circuit with $$N$$ nodes, let vector $$v$$ represent the respective node

voltages. For ease of representation we model a circuit with capacitors and

voltage controlled resistors. Then applying `KCL` (Kirchoff's Current Law) to the

circuit yields the following systems of equations:

$$ f(v,t) = i(v(t)) + \frac{d}{dt}q(v(t)) + \int_{-\infty}^t{y(t-\tau)v(\tau)} +

i_{s}(t) = 0 $$

We let $$q$$ and $$i$$ represent the sum of the charges and currents entering the

nodes due to the non-linearities. $$y$$ is the impulse response matrix of the

circuit with all non-linearities removed while $$i_{s}$$ represents the external

source currents.

We then convert equation above into the frequency domain:

$$ F(V) = I(V) + ZQ(V) + YV + I_{s} = 0 $$

Here $$Z$$ represents a matrix with frequency coefficients representing the

differentiation step. The convolution integral in the equation above maps to `YV`

as shown where `Y` is the admittance matrix for the `linear` portion of the circuit.

`V` then contains the fourier coefficients of the voltage at each $$N$$ nodes at

every harmonic. This process is merely nothing more than `KCL` in the frequency

domain for `non-linear` circuits.

# Lumped and Distributed Element Networks

As mentioned above, as the size of a circuit element starts to approach a

fraction (typically `1/10`) of the wavelength of the highest `RF` signal frequency,

the lumped element approximation for the circuit element no longer holds. In

these cases lumped or discrete components cannot be used and so a distributed

element/model must be utilized.

Traditionally the use of lumped element components at `RF` frequencies is most

common below around `500 MHz`. Above `500 MHz` these lumped circuit

elements become more difficult to design with.

# Classes Of Operation

Depending on the `DC` operating point of the power transistor, different values of

efficiency and output power can be obtained for the same input power. Efficiency

is generally considered the most important design parameter for an `RF` power

amplifier.

In the `class-A` configuration the transistor is biased such that the quiescent

drain current is equal to the peak amplitude of the current expected through the

load. This allows for a symmetrical voltage and current swing at the output and

the transistor conducts for the full `360` degrees of the input waveform.

The advantages of this configuration are excellent linearity and gain at the

expense of reduced efficiency. A `class-A` power amplifier with an inductively

loaded drain has a maximum theoretical efficiency of `50%`.

`Class-B` power amplifiers aim to achieve greater efficiency by only conducting

for half of the input drive cycle (`180` degrees). `Class-B` power amplifiers have a

maximum theoretical efficiency of `75%` and the transsitor is biased at cutoff.

Again `class-B` `PA's` can be placed in a single-ended configuration or push-pull.

The advantage of `class-B` are increased efficiency at the expense of decreased

linearity.

A compromise is thus needed between `class A` and `class B` such that we have

sufficient linearity at a reasonable efficiency. A `class-AB` power amplifier is a

solution to this problem.

In the `class-AB` mode of operation the transistor is biased with a quiescent

drain current slightly to moderately above cutoff, depending on the linearity

requirements. This improves the linearity of the power amplifier while typically

maintaining an efficiency of `50%` to `70%` in practice. `Class-AB` power

amplifier's have a conduction angle between `180` and `360` degrees.

The `single-ended`, `class-AB` mode of operation is therefore a popular choice

amongst designers.

# Stability Analysis

`RF` power

amplifier's are inherently unstable devices which often require some form of

stabilization to operate correctly.

Amplifier instability is usually caused by some type of gain and feedback

mechanism. In `MOSFET` transistor's the feedback mechanism is typically due to the

gate to drain capacitance that couples a portion of the output back into the

input and vice versa. This effect often manifests as unwanted oscillation at

either the input and output of the PA.

Small signal parameters (such as `S-parameters`) are typically used to

characterize stability of `RF` power amplifier's even though these are `non-linear`

devices. This is because small signal models can still provide useful insights

into the design of a `PA` without requiring complex non-linear calculations.

Typically the operation of a `PA` is linearized around an operating point.

There are various stability factors available to a designer and an amplifier may

be conditionally stable or unconditionally stable. If an amplifier is

conditionally stable then there exists a load and source impedance that causes

the amplifier to oscillate. Therefore unconditional stability is usually

desired.

The most common stability factor in use is the `Rollet` stability factor ($$K$$)

which is defined as follows:

$$ K = \frac{1 - |S_{11}|^2 - |S_{22}|^2 + | \Delta |^2}{2|S_{12}S_{21}|} $$

Here $$\|\Delta\|$$ is defined as the scattering-matrix determinant:

$$ | \Delta | = |S_{11}S_{22} - S_{21}S_{12}| $$

We define three more stability Criterion in terms of $$\Delta, B_{1}$$ and

$$B_{2}$$:

$$ B_{1} = 1 + |S_{11}|^2 - |S_{22}|^2 - |\Delta|^2 $$

$$ B_{2} = 1 + |S_{22}|^2 - |S_{11}|^2 - |\Delta|^2 $$

In order for an amplifier to be conditionally stable we require the

following conditions:

$$ K \ge 1 $$

$$ \Delta < 1 $$

$$ B_{1} > 0, B_{2} > 0 $$

# Efficiency

The most common measure of `RF` power amplifier efficiency is $$PAE$$

(power added efficiency) and is defined as follows:

$$ PAE = \frac{P_{out} - P_{in}}{P_{DC}} $$

Here $$P_{in}$$ represents the `RF` input power from the source, $$P_{out}$$

represents `RF` power delivered to the load and $$P_{DC}$$ represents the total `DC`

power.

# P1dB Compression Point

The `P1dB` point is defined as the output power level at which

the gain of an amplifier decreases by `1 dB` from its nominal value which

indicates the onset of gain non-linearity.

Most amplifier's start to compress approximately `5` to `10 dB` below their `P1dB`

point.

The `P1dB` point indicates that power amplifier's have a linear and non-linear

region of power gain.

# Load Pull

`Load-pull` is an empirical `RF` `PA` design technique in which the

reflection coefficient or impedance presented to the drain of a `RF` power

transistor is varied by an electrical or mechanical impedance tuner to any

arbitrary value. The technique is traditionally used to determine the optimum

load impedance to present to an `RF` power amplifier for maximum output power.

Once the optimum load impedance is determined the synthesis of matching networks

can then take place. `Load-pull` tuners are expensive devices and are therefore

typically out of the reach of most students or experimenters.

In the case where a physical `load-pull` tuner is not available and a `non-linear`

model for the chosen `RF` power transistor exists, then a simulated `load-pull` can

be performed.

# LC Filtering

As `non-linear` devices, power amplifiers typically produce

harmonic frequency content that must be filtered out in order to comply with

regulatory standards on spurious emissions. `LC` networks can be constructed with

varying number of elements (poles) in order to achieve a specific roll-off in

the stop-band.

Two types of filter response are commonly used in `RF` circuit design, these are

the `Chebyshev` and `Butterworth` responses. `Chebyshev` `LC` filters typically have a

steeper roll-off but suffer from passband ripple.

`Butterworth` `LC` filters typically have a flat response in the passband with a

gradual roll-off in the stop band. These types of filters can be designed

manually using filter constants or using `RF` design software such as `Matlab` (`RF

Toolbox`) and typically an optimization algorithm. We typically optomize for

either stopband attenuation or input impedance.

That concludes this journal entry! I have just touched on some basic principles that

might help with understanding more advanced concepts.

# Signature

```

+---------------------------------------+

| .-. .-. .-. |

| / \ / \ / \ |

| / \ / \ / \ / |

| \ / \ / \ / |

| "_" "_" "_" |

| |

| _ _ _ _ _ _ ___ ___ _ _ |

| | | | | | | \| | /_\ | _ \ / __| || | |

| | |_| |_| | .` |/ _ \| /_\__ \ __ | |

| |____\___/|_|\_/_/ \_\_|_(_)___/_||_| |

| |

| |

| Lunar RF Labs |

| https://lunar.sh |

| |

| Research Laboratories |

| Copyright (C) 2022-2025 |

| |

+---------------------------------------+

```

|